The international development community will always look back on 2010 as a banner year for development policy in the United States. It was the year when development was first recognized as a pillar of national security. It was the year of the first ever-Presidential Policy Directive on Global Development. And it was the year of the State Department's first Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review.

So yeah, a lot happened in 2010.

As an implementer in the field, though, I will always look back on 2011 as the real banner year. 2011 is when USAID translated all of the new high-level development policy work from 2010 into operational guidance for USAID’s staff and implementing partners. 2011 is when the rubber hit the road. Specifically, the USAID Policy Framework introduced in September of 2011 laid out seven new operating principles to shape the Agency’s strategies and guide its programming. These seven operating principles were:

- Promote Gender Equality and Female Empowerment

- Apply Science, Technology, and Innovation Strategically

- Apply Selectivity and Focus

- Measure and Evaluate Impact

- Build in Sustainability From The Start

- Apply Integrated Approaches to Development

- Leverage “Solution Holders” & Partner Strategically

This was all taking place around the time that USAID launched the Southern Africa Trade Hub (the Trade Hub) in late 2010, a project that I have been working on in various capacities over the last several years. One of the Trade Hub’s highest profile accomplishments stands out as an example of what a project can do at the programmatic level when USAID’s operating principles are used to shape the design of development assistance. For today’s blog post I thought I would share the story behind the success. I’ll start with a little background for context.

Background

South Africa has historically been home to a vibrant manufacturing industry and among the industries where it was always particularly strong was the manufacturing of textiles and apparel. In the late 1990s, however, South Africa’s textiles and apparel industries started to decline and by the end of 2010 South Africa’s industry looked like it was on the verge of collapse.

The implosion was driven by several factors, but the straw that broke the camel’s back was the 2005 expiration of the WTO’s Multi Fibre Arrangement (MFA) that had kept large quantitative ceilings in place to restrict Chinese exports. The quotas had been used primarily to protect the large developed markets in the US and Europe, but they had indirectly assisted South African companies by protecting them from the threat of highly competitive apparel imports. Once those MFA quotas expired the global apparel industry became exposed, virtually overnight, to China’s unparalleled competitiveness in apparel. Between 2001 and 2010 South Africa went from being a net exporter of apparel to a net importer. South Africa finished the 00's with a trade deficit in apparel of over $1 billion.

And the turmoil was not isolated to South Africa - it hit the entire region of Southern Africa. For decades many of the smaller countries of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) had also been producing apparel. Several of these countries had even been manufacturing apparel for export. Countries like Mauritius, Lesotho and Swaziland - and even South Africa to some extent - had originally benefitted from the MFA because the imposition of the quotas back in the mid 90s had driven much of the apparel manufacturing capacity in the large quota-constrained producers to smaller, less developed countries.

Not surprisingly, the chain of events that had crippled South Africa’s industry wreaked the same kind of havoc on the smaller apparel-producing countries in the region, and this is where things stood with the textiles and apparel industries in Southern Africa when USAID launched the Southern Africa Trade Hub (Trade Hub) program in September of 2010.

Opportunity Knocks

The situation was clearly grim at the time, but when the Trade Hub looked at all the carnage that had taken place across the textiles and apparel industries in Southern Africa they saw an interesting development opportunity emerging.

The opportunity that the Trade Hub saw for Southern Africa was linked to events unfolding in China. Production costs had been increasing in China because its labor markets had started tightening. Sustained periods of high growth had created a massive domestic market for apparel in China, and this new demand had started competing for China’s historically export-oriented output. Finally, Chinese companies had started turning down small orders because they could no longer compete on price without the full use of their production lines. The door had started opening for other apparel producing countries to compete on a niche basis with China.

This was a particularly big deal for Southern Africa. Cheap Chinese apparel imports were largely responsible for the implosion that had taken place in South Africa’s textiles and apparel industries. China’s exports of apparel to Southern Africa had grown tenfold the past decade - from around $100 million in 2001 to over $1 billion in 2010.

From the Trade Hub’s perspective, the picture was clear:

- South Africa - the largest economy in Sub Saharan Africa - was importing over $1 billion of apparel every year, mostly from China.

- Production costs in China were on the rise and Chinese manufacturers were starting to turn down the kind of small orders/limited production runs that typified many of South Africa’s apparel imports.

- South Africa’s neighbors - especially Lesotho, Swaziland, Madagascar and Mauritius - had both apparel manufacturing skills and under-utilized production capacity.

Put these three things together and the solution is clear right? Love Thy Neighbor!

What South Africa really needed was a way to bring the region’s apparel manufacturers to their doorstep. In fact the need for a new regional trade platform around textiles and apparel was so clear and compelling that the Trade Hub made it the cornerstone of the project's support for textiles and apparel.

Putting The Principles To Work

Remember that the whole point of this blog post is to highlight how the Trade Hub was able to embrace the new operating principles from USAID’s Policy Framework that had just been released to guide the design and implementation of Source Africa. I’ll tell the story by describing how it came together in the context of three of USAID's principles.

By making “apply selectivity and focus” one of its seven core operating principles in 2011 it is clear that USAID was asking its staff and implementing partners to do a lot more homework in the design phase of a program to figure out specifically where it would be possible to generate impact, and to focus resources on those areas. In the context of the Trade Hub’s work in textiles and apparel what this meant was figuring out which export markets provided the strongest opportunities for the region’s apparel manufacturers.

Here it is important to keep in mind that USAID's Trade Hubs had all originally been set up as mechanisms to help countries in Sub Saharan Africa increase their exports to the United States under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). So, to even consider selecting - and focusing on - an export market other than the United States would have been unheard of before USAID made “apply selectivity and focus” one of its seven core operating principles in 2011.

The reality back at that time was it made little sense to focus any significant resources in Southern Africa on promoting exports of apparel to the United States under AGOA because of recent market conditions in the US, political uncertainty around whether the US would be renewing AGOA, and some lingering non-tarrif barriers related to the overall enabling environment in Southern Africa. Of course promoting trade to the US under AGOA would still be part of the platform, it just could not be the core focus back then because promoting trade under AGOA had a long fuse to results ... the fuse to results in South Africa was a lot shorter. (A lot has changed with regard to the US Market and AGOA since then)

There was also an undercurrent at the time in the region’s industrial policy. A body of research that was reshaping the developing world’s perspective about big, global value chains had caught the attention of policy makers across SADC. This research was suggesting that global consolidation, asymmetric markets and evolved power structures were all increasing entry barriers, and making the upgrading process more complicated and contested in global value chains like apparel. And, the research was also pointing out how growth in end markets of the large developing countries (like South Africa) offered more attractive “regional“ opportunities for exporters. A prominent regional economist at the University of Cape Town was spearheading a lot of the research, and thereby drawing attention of regional policy-makers towards South Africa as one regional market where the benefits of up-gradation and spillovers seemed more likely, and more accessible.

Ultimately it was the confluence of all these issues, in aggregate, that pushed the Trade Hub to look at South Africa’s market as the best opportunity for the region’s textiles and apparel industries to have a significant and measurable impact over the life of the program.

Operating Principle #2 - Leverage “Solution Holders” and Partner Strategically

Once the Trade Hub had identified South Africa as its anchor market for promoting trade in textiles and apparel, the next step was identifying a "solution holder” to work with. In this case what the Trade Hub needed was an organization that could assemble the entire complex array of South African apparel buyers and engage them with the region's manufacturers. Where do you find that? How about the company that had been putting all those Chinese manufacturers together with South African buyers over the past ten years? That’s exactly who the Trade Hub found.

The Trade Hub identified Leaders in Trade Exhibitions of South Africa (LTE) as the solution holder. LTE is a small, woman-owned South African event management business that has specialized in trade exhibitions for the textiles, apparel and footwear industries in Southern Africa since the mid 1990s. At the time LTE had been running the ATF Expo in South Africa for almost fifteen years. The ATF Expo had become the premier forum in South Africa where international exporters of textiles, apparel and footwear from all over the world came to South Africa every year to showcase their products for South African buyers.

That’s the key thing that LTE brought to the table for the Trade Hub - LTE brought a vast network and relationships with South Africa's apparel buyers. Over a 20 year period LTE had built connections with sourcing heads, merchandizers and technologists from all of South Africa’s chain stores, independent retailers, boutiques, distributors, wholesalers, importers, agents and manufacturers. In other words, if you were an apparel manufacturer that had started exporting to South Africa over the past 20 years there’s a very good chance that your connection to South African buyers was initiated through a platform established by LTE.

And I think the Trade Hub had a great pitch to get LTE interested. “Let’s join forces so we can do for the countries of Southern Africa over the next ten years what you’ve done for China and the rest of Asia over the last ten.” Both sides were clearly interested. The hurdle was figuring out how to get it done.

Operating Principle #3 - Build in Sustainability from the Start

USAID and its implementing partners have been hosting conferences and events, organizing buyer/supplier meetings, and sending beneficiaries to international trade shows for decades. While this classical type of donor-funded support is generally always positive in terms of outcomes, and sometimes leads to measurable results in terms of linkages and sales, it has always had issues in terms of sustainability. Well, the guidance coming out through USAID’s new Policy Framework was clear. The Trade Hub had to build in sustainability from the start - and that required a new way of thinking.

The Trade Hub determined that the best way to make its initiative sustainable from the start was to begin with the end in mind. The process of imagining the end up front led to two important decisions. First, the Trade Hub asked LTE to assume complete ownership of the event from day one. In fact, the very first bullet point of the Trade Hub’s MoU with LTE required LTE to register all the intellectual property associated with the event in its own name. Second, the agreement clearly specified that while the Trade Hub would assist with certain elements of the event, LTE as the event owner would assume full financial responsibility for the costs of the Trade Show and full financial risk associated with the event.

It is difficult to put in words how much of a departure this kind of arrangement was from the conventional way of doing things with USAID programs. Instead of having USAID own, control, staff, and finance the activity, the Trade Hub decided to put a local partner in the drivers seat on day one. It was an unconventional move, but it was the move that made the most sense given USAID's new operating principles, because it meant that from day one decision-making about the event would made on a commercial basis.

Results

Once LTE and the Trade Hub had reached an agreement everyone went to work to put together the first event. The first production of Source Africa was held in Cape Town, South Africa in April 2013. USAID, the Government of South Africa, Enterprise Mauritius, and several other regional stakeholders across the industry all lauded Source Africa as a visionary platform and tremendous success. The second and third productions of Source Africa were held in June 2014 and June 2105, both again in South Africa’s mother city of Cape Town. The last event attracted 226 exhibitors and more than 1300 visitors from 28 different countries.

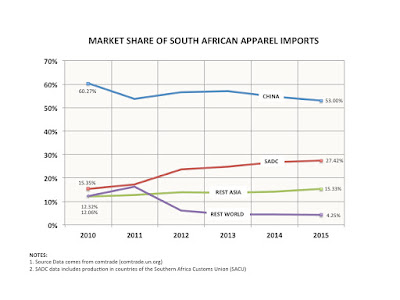

While each Source Africa event has certainly promoted global exporting opportunities with the inspired support of the American Apparel and Footwear Association (AAFA), and while each event has attracted interest from buyers representing both the US and European markets, the commercial success of the event thus far is clearly linked to its facilitation of regional trade opportunities within Southern Africa. The exhibit below shows why (click to expand).

Annual exports of apparel to South Africa from its SADC neighbors more than doubled between 2010 and 2015, an increase of US $243 million. And over the past five years South Africa’s SADC neighbors have increased their share of South Africa’s apparel imports by 12 percentage points (from 15% to 27%). Over that same period China’s share of South Africa’s apparel imports decreased by 7 percentage points (from 60% to 53%). What is particularly interesting about the trend illustrated above is how little market share was gained by manufacturers from the emerging powerhouses in Asia (i.e. Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia.) In most large, developed markets the new Asian powerhouses have taken the predominant amount of China’s market share losses - that is not the case in Southern Africa.

Five years worth of data also provides the opporunity to look back and evaluate some of the team’s original instincts. In particular, I found it interesting to see if the data validated the team's decision to select, and focus on, the regional market instead of the US market given the prevailing circumstances at the time. As the exhibit below demonstrates the gains that SADC producers achieved in the South African market are about the same as all countries of Sub Saharan Africa combined were able to achieve in the US market under AGOA (click to expand).

Neither of these performances compare to the kind of apparel volumes that Asian manufacturers have been exporting to the world the last 10 years. But, when you look at African apparel manufacturing in the context of these two export markets the regional opportunities afforded by the South African market become undeniably clear. For Southern Africa, this is all a pretty big deal and it validates the Trade Hub's decision when they put the program together.

Now I don’t want to overstate the case. Yes, the doubling of SADC’s apparel exports to South Africa over the last five years is impressive, but it's not all just because of Source Africa. The trend started a couple of years before LTE put on the first Source Africa show. Source Africa’s contribution has been to provide a reliable platform every year for textile and apparel industry stakeholders across Southern Africa to gather and take care of business. Some people go to strengthen existing sourcing relationships. Some go to build new ones. Some go to offer technical assistance, or to sell fabric, or buttons. Some go to sell services. Some go just to check it all out because it’s in Cape Town, and because there’s a lot of interesting creative people hanging around. Some probably go because they have to check the box. The point is that a ton of people are going, more each year, and a lot of them every year.

Five years worth of data also provides the opporunity to look back and evaluate some of the team’s original instincts. In particular, I found it interesting to see if the data validated the team's decision to select, and focus on, the regional market instead of the US market given the prevailing circumstances at the time. As the exhibit below demonstrates the gains that SADC producers achieved in the South African market are about the same as all countries of Sub Saharan Africa combined were able to achieve in the US market under AGOA (click to expand).

Neither of these performances compare to the kind of apparel volumes that Asian manufacturers have been exporting to the world the last 10 years. But, when you look at African apparel manufacturing in the context of these two export markets the regional opportunities afforded by the South African market become undeniably clear. For Southern Africa, this is all a pretty big deal and it validates the Trade Hub's decision when they put the program together.

And the best part of it all is that Source Africa is already financially self-sustaining ... and it only took three years. I’m still shocked. In the 20 years that I’ve been doing this work I’ve never seen anything like it happen.

- Drew Schneider