Taking a little detour with my blog today to outline a "model approach" for private sector development that distills my knowledge and experience into a single, replicable framework for action.

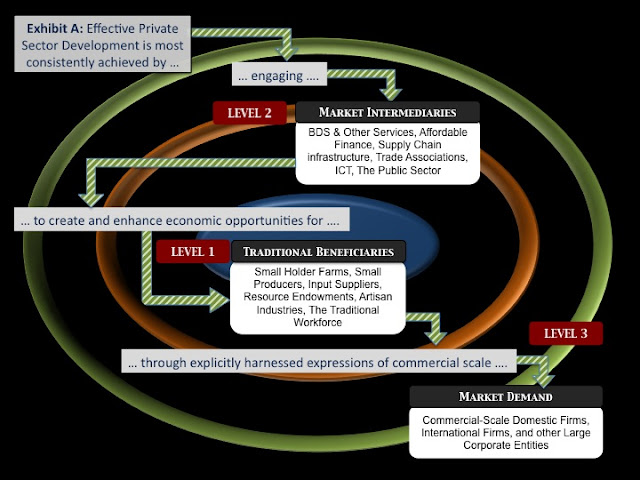

My experience suggests that effective private sector development is most consistently achieved by engaging market intermediaries to create and enhance economic opportunities for traditional beneficiaries through explicitly-harnessed expressions of commercial-scale market demand.

- Traditional Beneficiaries: This refers broadly to a host country's endowments and includes its most vulnerable economic actors. Traditional beneficiaries are those constituencies that are typically targeted in classic development programs. Some of the most common include: smallholding farms, small producers, artisan industries, input suppliers, and the traditional workforce. I refer to traditional beneficiaries as "Level I" in this conceptual framework.

- Market Intermediaries: This refers broadly to a host country's services sector. It captures the host country's economic actors that play key roles facilitating the growth of productive sectors and/or in driving growth in the new economy. Some of the most common market intermediaries include: business development services; trade associations; affordable finance; information and communication technology (ICT); supply chain infrastructure; and, public sector institutions. I refer to market intermediaries as "Level II" in this conceptual framework.

- Commercial-scale Market Demand: This refers generally to companies or other entities with commercial scale business operations. Commercial-scale market demand can be represented by both host country firms as well as multinationals operating in-country. I refer to commercial-scale market demand as "Level III" in this overall framework.

This is all captured graphically in the exhibit below:

The best way to explain the overall framework is by defining its core principles.

(1) In developed economies almost all production is demand-driven. About a year ago I asked an agricultural marketing specialist that I was working with to give me a simple definition of 'commercial agriculture.' Here's what he said; "Drew, commercial agriculture is when you plant your crops after you've identified your buyer." This general concept applies across the board in private sector development, not just commercial agriculture.The concept is important because it's what helps ensure relevance in end markets. Pre-production knowledge of demand is one of the key things that makes developed economies efficient. Effective private sector development ultimately boils down to building an economy's capacity to understand and better satisfy demand.

Of course there is really nothing revolutionary about this concept. "Demand-driven" has been emerging as a buzzword in our industry for well over a decade. The supply-side, demand-side struggle has actually been raging in intellectual circles for centuries. I'll never forget the day back in college when I was first introduced to French economist John Baptiste Say, and his 19th Century law stating; "Supply creates its own demand."

My professor, who obviously had some strong feelings on the subject, pulled something out of his briefcase and tossed it on the floor by his lectern. He said; "I've got a fresh supply of dog doo for sale here class; show me the demand!" A few of us laughed but nobody offered to buy the baggie of poo. Satisfied that he'd made his point our dear old professor turned around and went on to the next part of his lecture without missing a beat. That happened back in 1989. I'll always remember it as the day I decided I was a Keynesian.

The point of all this, aside from the fact that I've always wanted to share that story from my college days, is that I don't think there's any real rhetorical disagreement anymore, at least as far as development economics is concerned. Our community now refers to almost all new programs as being "demand-driven". The fact that a lot of "demand driven" projects out there are nothing more than re-branded versions of the same old "supply-driven" approaches seems a little disingenuous to me; but hey, at least we've all got the rhetoric right!

More on this issue when I dive into methodology in the next post. For now I'll wrap it up as follows:

Framework Principle #1: Effective private sector development programs are demand-driven. Proxies are not reliable mechanisms for expressing demand in developing economies; i.e. programs where demand is expressed through international sector specialists, local industry working groups, or "that's what worked in the last country" ... "that's all I had on my thumb drive" are not truly demand-driven. Real Demand-driven programs are contractually anchored to profit-motivated expressions of commercial-scale market demand already operating in the markets targeted for intervention; with some real skin in the game.

(2) If you haven't already, I encourage you to take a step back and find a way to get a handle on the profound relationship between economic growth and growth in services. If you look at the economic data underlying any contemporary development success story you will see that periods of sustained economic growth go hand in hand with dramatic growth in the services sector.

Of course it makes perfect sense. Close your eyes and try to imagine what is actually taking place in a country as the private sector develops. The image that comes to my mind is a viral explosion of new mechanisms that "connect the dots" between a country's old economy and new expressions of market demand. This viral explosion of connection mechanisms gets reflected in national economic data as growth in Services, while the compounding impact of the overall process gets reflected as growth in GDP. I've captured this all graphically in the following illustration:

The fact is most of the tangible results that we offer up as evidence of success for private sector development projects are the byproducts of new connection mechanisms established in our host countries. We have to keep in mind that that the evidence of new connection mechanisms are an important consequence of our work, but the evidence is not the objective. Neither are the new mechanisms themselves. Our ultimate objective in doing private sector development is strengthening a country's capacity to build its own new connection mechanisms on a sustained basis ... that's the only way the process becomes viral. We have to keep this distinction in the front of our minds as we implement projects so that we can stay focused on what we're ultimately trying to achieve.

Let's not kid ourselves. This is a tough thing to do right because it takes a lot of time, patience and persistence to do well. When it comes to choosing between building real sustainable local capacity and importing short-lived end-to-end solutions, international firms will always be conflicted as long as time is short, process is opaque, and expectations are high. Local firms, on the other hand, are not faced with the same choices. Local firms are more compelled to find ways to muddle through the reality of their own environments so they too can deliver evidence of success.

Framework Principle #2: The best private sector development programs blend in, use what's already there, and never let themselves get too intrenched or too far ahead. Just as growth in services tends to underpin growth in productive sectors, host-country service providers (in both existing and emerging forms) have got to be the 'workhorses' of program implementation. Programs should try to mimic, as much as possible, the way a system is expected to function once the donor support goes away.

(3) The third key to understanding my framework is resisting the natural tendency to snap to judgement when you realize that it is explicitly structured to make big, successful companies bigger and more successful. I was discussing this issue with my wife the other day, who happens to be one of the industry's real pioneers in the area of strategic communications. As I explained this point her brow started to furrow and she asked; "So exactly how is this different from 'trickle down economics'?" It was a great question, and an important one to answer, since philosophically speaking my framework for private sector development is a form of trickle down economics.

There are at least two key differences between this approach and a more conventional understanding of trickle down economics. The first big difference is that my approach is truly demand-driven and tailored at a micro-level; it has nothing in common with supply-side macro policy. The second big difference is that my approach involves carefully engineering each program to be inclusive at the outset; a far cry from cutting taxes on the wealthy, closing your eyes, and hoping for the best (whatever that might be).

Framework Principle #3: Programs have to be inclusive. Private sector development that does not involve a broad participation in the benefits of economic growth is rarely self-sustaining. Effective programs highlight paths of inclusion, and specify clear plans for validating and measuring target beneficiary impacts at set checkpoints along the way. Remember there is nothing intrinsically wrong with making strong companies stronger as long as the strength is not achieved through donor-funded market distortion. Pro-poor, inclusive development creates strength through increases in a host country's connective capacity, productivity, and the realization of unfulfilled market demand.

(4) Finally, we have to come to terms with the uncertainty inherent in the development landscape. There are so many different factors that can cause volatility in our implementing environment that you can't manage them individually. My approach is to key off of the macro-dynamics that are always at play, supported by tools to help monitor what's happening and navigate the way.

To keep track of what's happening and make sure your project stays relevant we need to understand the basic evolution of development theory and industrial policy, and appreciate some key lessons learned. The evolution of development thinking is often characterized as a struggle between competing sides of an ideological spectrum. The 'vertical integrators' were the first to set up camp. Using the Asian Tiger economies as the model, they subscribed to the idea that development is all about 'picking the winners'; i.e. that state-chosen firms and industries supported through subsidies and protectionist policies can mature, become competitive in regional and world markets, and drive a country's overall growth. On the other side of the spectrum, the 'horizontal integrators' rose to prominence as countries like Costa Rica and Ireland managed to put themselves onto new trajectories of growth. This competing school of though argued the virtue of free and efficient markets, investment-friendly enabling environments, and policies geared towards a correction of systemic market failure.

Over the last decade the theorists have discovered that in fact both schools are right ... and that both schools are also wrong. Neither of the two models could ever consistently explain, or anticipate, what makes economic development actually happen. The contemporary thinking incorporates parts of both schools of thought, and focuses extensively on important lessons learned. I think there are three lessons in particular that practitioners like us have to understand in order to effectively establish and manage our programs. They are:

- The realization that national economic systems are way too complicated for anyone to comprehensively understand and purposefully engineer, i.e. there is now a broad appreciation of development chaos theory - the fact that each time we introduce change it has the potential to fundamentally reshape relationships and incentives across the entire economic system.

- More pragmatism in terms of acknowledging the role that political economy plays in the development process, i.e. big-bang structural reform programs just aren't practical because any highly ambitious scope of reform is likely to undermine a sitting government's political support.

- A recognition of the importance of behavioral economics, i.e. shifting away from intervention that is limited to neoclassical forms of market failure, and towards approaches designed to ease more immediate, specific, relevant and practical constraints to development.

This overall concept is captured in the final principle.

Framework Principle #4: Funding for program activities should be structured in phases through competitive processes to ensure relevance. Mechanisms should also be established to make premature terminations of already pledged funding complicated and difficult. Effective private sector development programs respond effectively to evolutions in host-country markets and systems while simultaneously resisting winds of international political change.

Conclusion

To wrap this one up I'll summarize the pros and cons of adopting my framework by contrasting it with the industry's classical approach. The real differences are the role that real market demand plays in shaping program activities, and the level of engagement with traditional beneficiaries (i.e. directly or indirectly). These distinctions are captured graphically in the exhibit below.

Our industry has historically preferred the "inside out" approach largely because the programs are quick to design, easy to replicate, and straightforward to implement. The programs also make it easy to spend pre-planned amounts on a fixed schedule, and they generate heartwarming stories that makes public relations and outreach fairly easy ... at least in the short run. The problem with these classical direct support programs is that they rarely lead to any significant, meaningful impact, and whatever impact the programs do achieve is rarely sustainable by markets over time. Remember Says Law, my college professor, and the baggie of dog poo? The differences between my approach and the classic approach may not be quite that black and white, but there's no question that the old model is "supply-side" at its core.

Things change pretty dramatically when turn the approach "outside-in.". Programs that follow an outside-in (i.e. truly demand-driven) approach have a much stronger likelihood of being effective and having a sustained impact. The downside is that they are harder to design, they are complex to set up, and they take longer to implement. The outside-in framework also makes it difficult to spend project funds on a fixed schedule, and it can expose programs to "trickle down" criticism that makes public relations a lot more challenging. The fact is there are some real tradeoffs involved in adopting the "outside in" approach. It's better development, but its more politically risky. It begs the question; "what's the right way to proceed?"

I can't answer that question for you. The path towards more effective development is one that you must choose to walk down at your own risk, and you should do it with your eyes wide open.

- DS